Inside this Issue

- A1 - Washington State DOT v. Seattle Tunnel Partners: Appellate Court Affirms Denial of DSC Claim Involving Tunnel Boring Machine

- A2 - Uninsurable Duty Under Compliance with Law Clause

- A3 - Prime Breached Good Faith Duty to Tender Subcontract Claim to Owner

- A4 - Arbitration Award Confirmed by Court

Article 1

Washington State DOT v. Seattle Tunnel Partners: Appellate Court Affirms Denial of DSC Claim Involving Tunnel Boring Machine

See similar articles: DOT | Latent Conditions | Tunnel Boring

Article by David Hatem

In a June 14, 2022 Unpublished Opinion, the Court of Appeals of the State of Washington in Washington State Department of Transportation v. Seattle Tunnel Partners, No. 54425-3-11, 2022 WL 2132780, (Wash. Ct. App. 2022), (“WSDOT-STP”) affirmed a Trial Court judgment denying entitlement of a Design-Builder’s differing site condition (“DSC”) claim. The WSDOT – STP litigation arose out of the Alaskan Way Viaduct project, in Seattle, in which WSDOT, as project Owner, awarded a design-build contract to STP, as Design-Builder, for the design and construction of a tunnel. In the procurement process, WSDOT provided proposers with multiple reports, some of which were classified as Contract Documents, while others were classified as merely Reference Documents, i.e. which were provided for information but were not part of the Contract Documents. During tunneling, STP’s tunnel boring machine (“TBM”) encountered Test Well 2 (“TW-2”), a pipe that had a 3/8-inch-thick, eight-inch diameter, steel well casing. That encounter resulted in the suspension of tunneling due to damage to the TBM and the need for its repair. STP submitted to WSDOT notice of a DSC on the basis that TW-2 was not properly or fully identified in the Contract Documents.

The Contract Documents defined a DSC as “actual subsurface or latent physical conditions at the Site that are substantially or materially different from the conditions” indicated in the GBR or GEDR (i.e., the Contract Documents). The GBR instructed that the GBR “must be read in conjunction with the GEDR.” STP’s DSC claim was denied by WSDOT and the dispute proceeded to litigation and trial. The Trial Court entered judgment denying DSC entitlement, and STP appealed. The appellate court rejected all STP arguments and sustained the trial court decision.

Read Entire Article by David Hatem

This article is published in ConstructionRisk Report, Vol. 24, No. 6 (July 2022).

Copyright 2022, ConstructionRisk, LLC

Article 2

Uninsurable Duty Under Compliance with Law Clause

See similar articles: code | Compliance with Law | law | Warranty

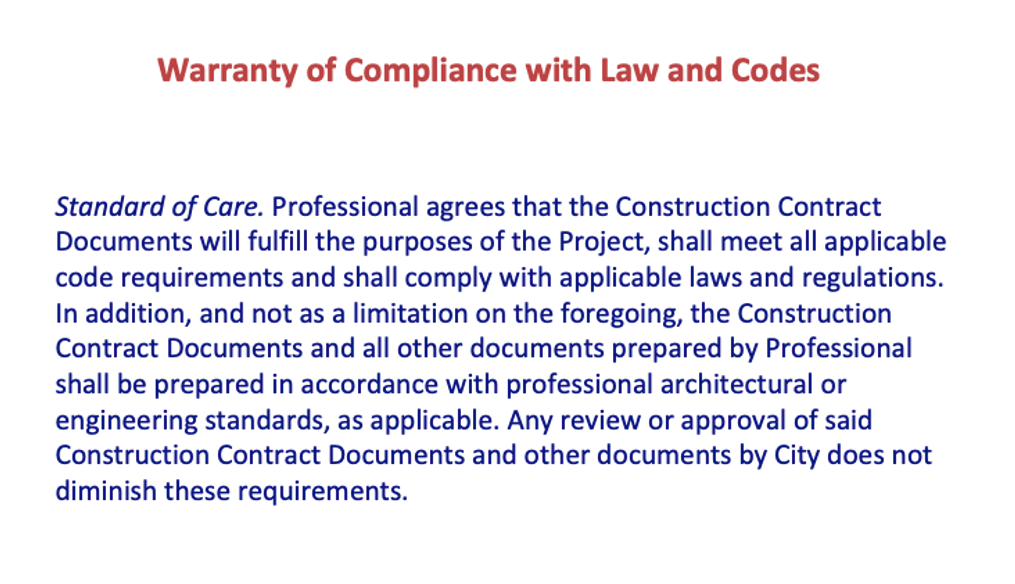

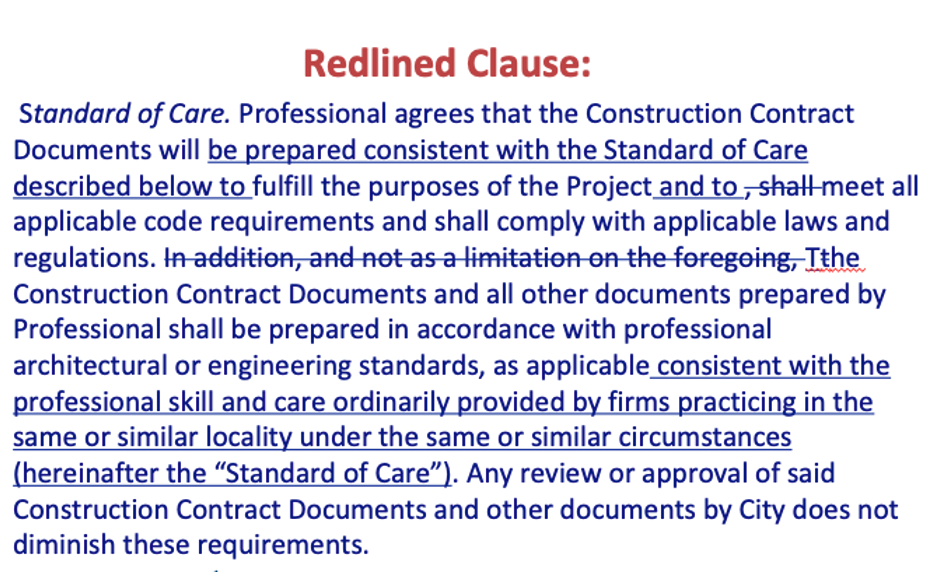

Professional services contracts typically include a clause stating that the consultant shall provide all services consistent with all laws, regulations, ordinance and codes. Although this may seem like an appropriate requirement, it could create an uninsurable warranty. The duty is made absolute. It is not conditioned on the designer following the Standard of Care. This becomes an uninsurable express warranty. How can it be remedied in the contract? Make compliance with law subject to the exercise of the Standard of Care. That’s insurable. See the short ConstructionRisk, LLC video on this subject.

Risk Management Comment:

An example of an uninsurable warranty of code compliance can easily occur with regard to fire code issues. I have represented consulting firms that were required to compensate their owner/clients for damages because the Owner was required by the fire marshal to change things in a building based on the fire marshal’s interpretation of code requirements – which code interpretation was not what would have been expected of a consultant exercising the reasonable standard of care. Likewise, building inspectors can interpret codes more stringently than a consultant might reasonably expect. Again, this can result in significant costs being incurred to correct something that the consultant believes met the standard of care. Unless the clause makes compliance with laws and codes a matter of exercising the standard of care, the consultant may be unable to defend itself with expert witnesses testifying that it acted reasonably in its code interpretation that differed from that of the code official.

About the author: Article written by J. Kent Holland, Jr., a construction lawyer located in Tysons Corner, Virginia, with a national practice (formerly with Wickwire Gavin, P.C. and now with ConstructionRisk Counsel, PLLC) representing design professionals, contractors and project owners. He is founder and president of a consulting firm, ConstructionRisk, LLC, providing consulting services to owners, design professionals, contractors and attorneys on construction projects. He is publisher of ConstructionRisk Report and may be reached at Kent@ConstructionRisk.com or by calling 703-623-1932. This article is published in ConstructionRisk Report, Vol. 24, No. 6 (July 2022).

Copyright 2022, ConstructionRisk, LLC

Article 3

Prime Breached Good Faith Duty to Tender Subcontract Claim to Owner

See similar articles: fair dealing | good faith | Pass-through Claim

Subcontractor was granted summary judgment on its suit against Prime to recover damages for Prime’s failure to prosecute a pass-through claim for delay damages against the City of New York. Court stated that the claim against the Prime was not barred by the no-damages-for-delay clause in the Prime Contract. Here, the Prime failed to timely prosecute the claim against the City resulting in it being dismissed. Prime also breached its duty of good faith and fair dealing when it filed to inform the Subcontractor of a settlement with the City and failed to provide the Sub any proceeds from that settlement. Rad & D’Aprile, Inc., v Arnell Construction Corp., 163 N.Y.S. 3d 653 (2022).

The plaintiff established that the defendant breached the implied covenant of good faith and fair dealing by failing to timely prosecute the plaintiff's pass-through claim against the City. The implied covenant of good faith and fair dealing between parties to a contract embraces a pledge that neither party shall do anything which will have the effect of destroying or injuring the right of the other party to receive the fruits of the contract. It encompasses any promises that a reasonable person in the position of the promisee would be justified in understanding were included…. The covenant of good faith and fair dealing required the defendant to take all reasonable steps so that the plaintiff's right to an eventual recovery, if any, from the City would be protected…. Here, the defendant did not take all reasonable steps to protect the plaintiff's right to recovery….”

Comment: This decision shows the importance of the doctrine of good faith and fair dealing. This duty is imposed by common law on the parties even when the contract does not expressly state that duty in the text.

About the author: Article written by J. Kent Holland, Jr., a construction lawyer located in Tysons Corner, Virginia, with a national practice (formerly with Wickwire Gavin, P.C. and now with ConstructionRisk Counsel, PLLC) representing design professionals, contractors and project owners. He is founder and president of a consulting firm, ConstructionRisk, LLC, providing consulting services to owners, design professionals, contractors and attorneys on construction projects. He is publisher of ConstructionRisk Report and may be reached at Kent@ConstructionRisk.com or by calling 703-623-1932. This article is published in ConstructionRisk Report, Vol. 24, No. 6 (July 2022).

Copyright 2022, ConstructionRisk, LLC

Article 4

Arbitration Award Confirmed by Court

See similar articles: AAA | Arbitration | Attorneys Fees

Arbitrator awarded attorneys fees to one party in an action. This decision was appealed and the appellate court affirmed, holding that the arbitrator at least arguably construed the parties’ agreement in awarding attorneys fees and expert costs to one of the parties. “Whether the arbitrator’s interpretation is correct is not a question before this court. Convincing a court of an arbitrator’s error – even his grave – error is not enough…. The potential for those mistakes is the price of agreeing to arbitration.” Industrial Steel Construction, Inc. v. Lunda Construction Company, 33 F.4th 1038 (2022).

In the contract between Lunda, the general contractor (GC) and its subcontract supplier (ISC), the contract expressly stated that the Subcontractor would be entitled to recover its reasonable attorneys fees if it prevailed in arbitration. But the parties negotiated to strike out similar wording for the GC. Despite the contract wording, the arbitrator awarded the GC its attorneys fees as part of the arbitration award. There was no detailed explanation in the arbitration decision for why that was done.

In analyzing whether the arbitrator abused its authority when it awarded those fees to the GC, the court explained:

“The AAA Construction Industry Rules also speak to the issue of fees and costs. Rule 48(d)(ii) provides that the “award of the arbitrator may include ... an award of attorneys’ fees if all parties have requested such an award or it is authorized by law or their arbitration agreement.” Rule 48(c) instructs that “the arbitrator shall assess fees, expenses, and compensation as provided in” Rules 55, 56 and 57. As relevant here, Rule 56 provides that “[t]he expenses of witnesses for either side shall be paid by the party producing such witnesses,” but Rule 48(c) permits the arbitrator to “apportion such fees, expenses, and compensation among the parties in such amounts as the arbitrator determines is appropriate.”

In seeking vacatur of the attorney's fee and expert costs, ISC relies on Section 10(a)(4), which permits vacatur “where the arbitrators exceeded their powers, or so imperfectly executed them that a mutual, final, and definite award upon the subject matter submitted was not made.” “A party seeking relief under that provision bears a heavy burden.” Oxford Health Plans LLC v. Sutter, 569 U.S. 564, 569, 133 S.Ct. 2064, 186 L.Ed.2d 113 (2013). “Because the parties bargained for the arbitrator's construction of their agreement, an arbitral decision even arguably construing or applying the contract must stand, regardless of a court's view of its (de)merits.” Id. (quotation omitted). Therefore, the “sole question” for the court is “whether the arbitrator (even arguably) interpreted the parties’ contract, not whether he got its meaning right or wrong.” Id. “An arbitrator does not ‘exceed his powers’ by making an error of law or fact, even a serious one.”

In this case, the court held that the arbitrator at least arguably construed the parties’ agreement when it awarded the attorneys fees. “’[T]he Arbitrator has reviewed R-48 of the Construction Industry Rules of the AAA and finds that an award of attorneys’ fees and costs is appropriate in this matter.’” The parties’ agreement provided that those rules would govern any procedural matters not otherwise specified in the contract. And the mention of ISC's liability for Lunda's attorney's fees was stricken from the parties’ agreement. Thus, we can conclude that the arbitrator at least arguably construed the agreement not to address Lunda's fees, determined liability for fees to be a “procedural matter not specified” in the agreement, and applied the Construction Industry Rules to fill in the gap, as provided by the contract.”

Here the court stated: “ISC may wish that the arbitrator had explained his reasoning in greater detail, but it does not offer any basis to conclude that “the arbitrator based his decision on some body of thought, or feeling, or policy, or law that is outside the contract.” “Where the reasoning of the final award provides “an interpretive route” from the contract to the arbitrator's conclusion, the district court may not vacate or modify the award, even if the district court disagrees with the arbitrator's ultimate conclusion.”

Comment: Parties should exercise caution when entering into contracts requiring them to arbitrate instead of litigate. At least in this particular case, the parties added wording to the contract requiring the arbitrator to issue findings of fact and conclusions of law – the arbitrator did so as to the merits of the underlying claims but failed to do so with regard to its reasoning for awarding attorneys fees. One thing that this decision shows is the great deference granted by courts to arbitration decisions. Unlike an adverse decision in a trial court than can be appealed to an appellate court, sometimes obtaining more favorable results, it is exceedingly difficult to reverse an arbitration decision with legal appeal.

About the author: Article written by J. Kent Holland, Jr., a construction lawyer located in Tysons Corner, Virginia, with a national practice (formerly with Wickwire Gavin, P.C. and now with ConstructionRisk Counsel, PLLC) representing design professionals, contractors and project owners. He is founder and president of a consulting firm, ConstructionRisk, LLC, providing consulting services to owners, design professionals, contractors and attorneys on construction projects. He is publisher of ConstructionRisk Report and may be reached at Kent@ConstructionRisk.com or by calling 703-623-1932. This article is published in ConstructionRisk Report, Vol. 24, No. 6 (July 2022).

Copyright 2022, ConstructionRisk, LLC

Connect